High Fantasy Book Club: Austerlitz — 00

Sebald's life, style, a really long German word // Book Club schedule

Hello and welcome to “session zero” for the first ever High Fantasy Book Club™, thank you all for being here, I’m so excited :). If this goes well, and everyone has fun, we’ll do another HFBC™ in the fall with the runner-up from the poll, Gene Wolfe’s masterpiece The Book of the New Sun. For this inaugural book club, however, we will be reading W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz, considered by many Sebald devotees (Sebaldiacs? Sebaldinis? Sebaldinis.) to be his crowning achievement. The first *real* discussion post about the novel will be in exactly one week, on Sunday, March 09. If you would like to go into the book as blind and unburdened as possible, or if you have already read other Sebald books, and little essays about his life, and his wikipedia page and so on and so on, scroll down to the end of this post to make note of the reading schedule.

I have not read Austerlitz, and I will make no claim to be an expert on Sebald (or any writer really, except maybe William Gibson lol), but after reading The Rings Of Saturn a few years ago, I became completely enamored with his hypnotic, discursive writing style and beautiful sentences, which has led me to figure out what I could about this absolute giant of modern letters. What follows is an inexhaustive, possibly occasionally incorrect primer on Sebald that compiles what I personally have been thinking of in the lead-up to this group read. If you think I have missed, or misrepresented something here, please chime off in the comments!

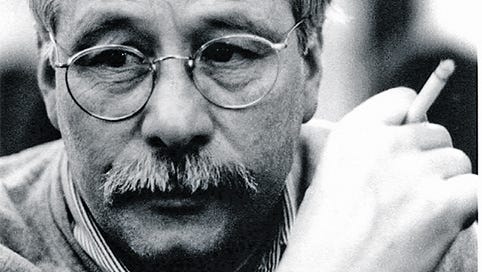

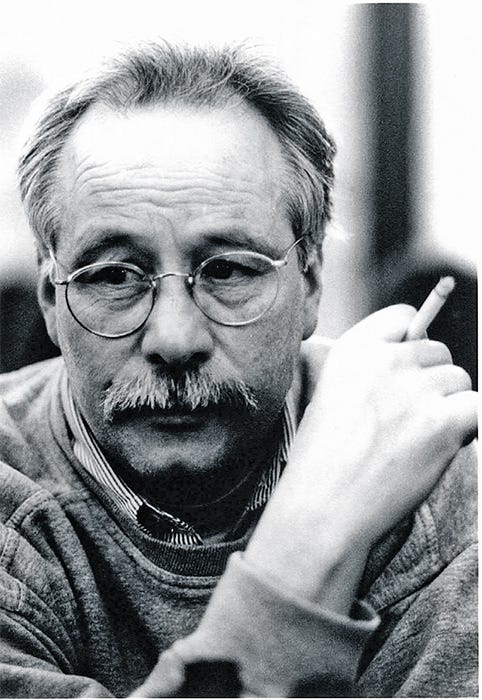

Who Was W.G. Sebald?

Sebald (pronounced ZAY-bald, not SEA-bald) was a private guy. As it stands now, there’s only one (unauthorized) biography of his life, and it has proven hugely contentious amongst the Sebaldinis, but the basics can be cobbled together thusly:

Winfried Georg Sebald, known to his friends as Max, was a German writer whose work spans poetry, criticism, essays and fiction, and whose four novels have achieved a cultish fandom around the globe. Born in Wertach, Bavaria in 1944. His father, Georg Sebald, served in the Reichswehr (the de-militarized Weimar army, akin to the JSDF) and later the Nazi Wehrmacht army, participating in the invasion of Poland in 1939, and later getting captured and held in a French POW camp until 1947. Sebald hated his father (part of why he went by “W.G.” was to minimize his father’s literal presence in his output), and related much more strongly to his maternal grandfather, a village constable named Josef Egelhofer. He studied literature in Freiburg (Germany) and then Friborg (Switzerland), and got his PhD from the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England.

He published his first novel, Vertigo, in 1990, his second, The Emigrants, in 1992, his third, The Rings of Saturn, in 1995, and his final novel, Austerlitz, in 2001. It was Austerlitz that brought him widespread fame and devotion, earning the National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction, and a host of other awards and top placements on various year/decade end lists. Part of the mystique and pull of Austerlitz is undoubtably due to the fact that Sebald died suddenly of heart failure just one month after Austerlitz was published, and mere days after its English translation hit shelves.

Oppa Sebald Style!

Sebald had a strong literary style that carried across all four of his novels, blending diaristic memoir-esque passages with long asides that take the form (but not necessarily the function) of non-fiction (a famous, maybe untrue anecdote about Sebald, involves him shrugging his shoulders and saying “fiction?” when his publishers asked how his work should be shelved). All of his books deal heavily with the property (literal, spiritual) of memory, and are dotted with mysterious, uncaptioned photographs. I won’t expound on the details of his style too much, as we will undoubtably be discussing his unique prose a lot as we read Austerlitz, and my goal with this “session zero” is to provide a little context and possible lead-off points, but there are some specifics regarding style that are worth discussing briefly ahead of getting into Austerlitz.

First, Sebald’s novels almost never have “plots,” which is not to say that nothing happens in his books, but rather that what does happens, happens in the past and is remembered, with present (to the novel) events generally serving only to trigger these remembrances, like the famous cake-dipped-in-tea that sets off Swann’s Way, and these tangential acts of remembrance form the core of what his novels ‘are.’

The other thing that I think is worth considering (though it will be lost entirely on us as readers of a work in translation), is that the German of Sebald’s fiction is intentionally archaic (as a loose comparison, consider the English deployed by Cormack McCarthy in Blood Meridian, influenced by Civil War the “Standard text of 1769” edition of the King James Bible and the Lattimore Odyssey), and his sometimes-pages-long sentences are apparently more a function of this old-fashioned German prosa than of modernist stylistic flourishes. I think this is worth keeping in mind because Sebald was fluent in English, wrote in English (and translated other writers from German) frequently, and was more than capable of self-translating.

The reasons he instead chose to rely on translators to bring his novels to the Anglosphere remain a mystery but they must exist, especially since he personally approved each translation of his four novels, corresponding and collaborating with the translators sometimes even before a book had reached its final form in the original German. I bring this up because the English of Sebald’s translated works, though often flowery, verbose, and melancholic, feels more-or-less contemporary, and does not read as archaic or old-world in style, despite this (apparently) being the case in German.

Vergangenheitsbewältigung

Vergangenheitsbewältigung is a German word that literally means “the work of coping with/overcoming the past,” and in practice is used almost exclusively to refer to “the work of coping with/overcoming having done the Holocaust.” The Second World War and the Holocaust loom large in all the Sebald I’ve read. Considering Sebald’s own parentage it comes as no surprise that seem that vergangenheitsbewältigung in its practical and, by extension, literal definitions, was a major driving force behind his literary output. As a German writer of the twentieth century, he was certainly not alone in this: themes related to vergangenheitsbewältigung— guilt, memory, intergenerational (particularly familial) estrangement— show up again and again in the many of the most celebrated literary works of the 20th century from the across much of the German-speaking (and indeed in Finnish, Hungarian, Estonian, Croat et al.) world.

Vergangenheitsbewältigung is also the flashpoint point for Sebald’s most vocal detractors. You cannot, of course, write about the Holocaust and it’s lingering effects without writing about Jewish experiences and for some readers and critics, Sebald’s blending of fact and fiction, particularly in regards to his focus on holocaust survivor’s lasting trauma and post-war Jewish immigrant experiences, veers towards the exploitative; that the ephemerality surrounding notions of “truth” in his novels is a cop-out that allows him to claim ownership of Jewish narratives, assuaging him of his guilt surrounding the actions of his father and the inaction of his extended family and loved ones.

These criticisms are interesting and not without merit, but for me personally it doesn’t do much to get in the way of Sebald’s impact or the sublime quality of his writing. That said, Austerlitz and it’s explicit handling of vergangenheitsbewältigung will be particularly interesting to read and discuss in 2025, given [Current Events] and our perspectives as Americans/Westerners more broadly situated in the heart of the Evil Empire™.

Reading Schedule:

In Thursday’s Book Club Update post, I mentioned that Austerlitz is divided into 15 parts. This isn’t really true: The entire book is one long passage, but it can be divided into 15 parts, and is commonly done so when the book is taught for a class. At any rate, here’s a tentative, incomplete schedule for the first two weeks:

Week One: March 09, 2025

pages 03—68, ending on “[…] his only early childhood memories.”Week Two: March 16, 2025

pages 68—138, ending on “[…] as it was of the Christian Faith.”

After two weeks, we can see how we all feel re: pace. I know everyone works, and is probably juggling Austerlitz with other books, but it’s possible we might want to speed up a little bit and get into the more ninety-to-one-hundred-ish pages a week, or even slow down to an even fifty or forty-five or something.

Please note that the page numbers listed are for the Modern Library paperback edition, which looks like this:

Okay, that’s it from me!! I turn it over to you all in the comments :)

Do you have your copy of Austerlitz yet? Have you read it before? Other Sebald? What do you make of it his work?

What does “Sebaldian” mean to you, and what expectations, hang-ups, etc (if any) do you have going into this book?

Thoughts on anything here? Do you disagree with anything I wrote? know why / have theories about why Sebald didn’t translate his own works?

Can you pronounce vergangenheitsbewältigung?1 I cannot!!

if you say yes, you have to send me a voice note proving it.

i’m gonna wait to read this until after i’ve started the book

*i’m looking forward to cracking up voice* i’m looking forward to finding out how much Jacques Austerlitz is like Lazsló Tóth

Literally zero book stores in the cursed city of Boston have this on their shelves 😡😡😡